Unity Interface

Contact Invariant Optimization

After spending two weeks (see previous posts) on implementing CIO, I start to feel unsure about its outcome. I completed all cost terms on Feb 18, and took a whole night to compute the first trajectory. The result was crazy.

Of course things won’t get right for the first time, and I may take great effort to fix every thing, with the cost of another two weeks. But I started to think about whether it’s worth doing so. On one hand, I have a tedious algorithm with unknown number of bugs to fix; on the other hand, I already have a read-to-use software that can generate legged motion very fast, but with some restrictions.

As the purpose of this project is to develop a tool that can synthesis the animation clips that can be used in motion matching, it’s better for it to be fast and interactive so that the tool can support iterative development. Which algorithm it uses doesn’t matter, as long as it can generate believable clips. In this case, Trajectory Optimization for Walking Robots by Alexander Winkler is a better choice.

Trajectory Optimization for Walking Robots

The software package includes an example with a command line interface and visualization. One can select one of its 4 robot models and see the generated trajectories on various terrains.

To be able to test the algorithm in an actual using scenario as soon as possible, I choose the simplest monoped model and the flat ground terrain. I compile the software into a library with release configure (so that it is fully optimized for speed). The following screenshot shows the computation time for a typical trajectory of 2 seconds.

I am surprised that it only took 0.2 second to compute a 2-second trajectory, which means that the optimization algorithm can be used in real-time, at least on the flat ground terrain. It has the restriction that the number of contact phase needs to be pre-determined, however, it doesn’t mean to be short of trajectory varieties. Its speed comes from that the structure (in terms of contact schemes) of the trajectory is pre-defined so that the algorithm only needs to refine its shape, and that its dynamics model is extremely simplified. The variety of the trajectory comes from its unique formulation of the optimization problem: it only specifies the constrains that must meet (dynamics, initial and final points), but doesn’t have a cost function. This leads to one of its features that it always generates a trajectory that is similar to the initialization. This also shows that good initializations make great differences to both the convergence speed and the solution quality.

C Interface

To make it a tool for game developers, it’s useful to make a compact C API for game engines to use. The exposed interfaces are listed below. The source code for the C library can be find here.

int create_session();

void end_session(int session);

struct Boundary {

double initial_base_linear_position[3];

double initial_base_linear_velocity[3];

double initial_base_angular_position[3];

double initial_base_angular_velocity[3];

double final_base_linear_position[3];

double final_base_linear_velocity[3];

double final_base_angular_position[3];

double final_base_angular_velocity[3];

double initial_ee_position[3];

double duration;

};

void set_boundary(int session, const Boundary* boundary);

// Start optimization asynchronously and return immediately, not blocking.

void start_optimization(int session);

struct Solution {

double base_linear_position[3];

double base_linear_velocity[3];

double base_angular_position[3];

double base_angular_velocity[3];

double ee_motion[3];

double ee_force[3];

bool contact;

};

// Returns true if the solution is ready, false if not.

bool get_solution(int session, double time, Solution* output);

bool solution_ready(int session);

The library is designed to handle optimization computations asynchronously, so that it won’t block the caller’s main thread. Thread safety is taken care of, so that callers from different threads can operate on one session.

Unity Interface

The next step is to call the functions from a game engine I am familiar with. In this project I choose Unity.

Unity is able to directly call into so-called native plugins, which are shared library complied for individual platforms. The process of interpreting C# data structures as those of foreign languages is called Marshalling, and this is the key to inter-language communication.

For example, suppose that hopper is the name of the shared library,

the structure Solution should be declared in C# as

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

struct _Solution

{

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.ByValArray, SizeConst = 3)] public double[] baseLinearPosition;

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.ByValArray, SizeConst = 3)] public double[] baseLinearVelocity;

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.ByValArray, SizeConst = 3)] public double[] baseAngularPosition;

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.ByValArray, SizeConst = 3)] public double[] baseAngularVelocity;

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.ByValArray, SizeConst = 3)] public double[] eeMotion;

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.ByValArray, SizeConst = 3)] public double[] eeForce;

public bool contact;

}

And the function get_solution declared in C should be declared in C# as

[DllImport("hopper", EntryPoint = "get_solution")]

static extern bool GetSolution(int session, double time, ref _Solution solution);

Coordinate Systems

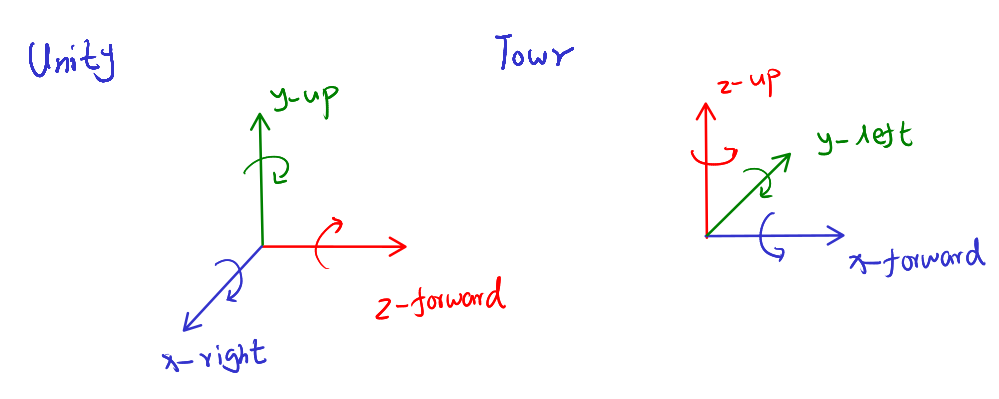

Another important thing is the difference between coordinate systems. Unity uses left-handed y-up coordinate system, while the algorithm uses right-handed z-up coordinate system. The differences between two are shown in the illustration below.

For vectors representing linear components (positions, linear velocities and forces), the transform is easy. Let $u$ denotes a vector in Unity and $v$ a vector in the library.

\[u = (-v_y, v_z, v_x), v = (u_z, -u_x, u_y).\]For angular components (rotations and angular velocities), that’s a little complicated. In the library, rotations are represented as intrinsic $zyx$ euler angles (yaw, pitch, roll). Unity document says that in Unity euler angles are applied in $zxy$ order. After testing, that’s an extrinsic order, so it’s actually in the order of intrinsic $yxz$, which makes it a lot easier for conversion because the orders are the same. So the conversion is given by:

\[u = (v_y, -v_z, -v_x), v = (-u_z, u_x, -u_y).\]Unity Real-time Application

I put a monoped into Unity and have it constantly go to the target. To keep it fast, I limit the maximum number of iterations to 20. It recalculates the trajectory once it reaches the end of previous one (that’s why it stuck for a while, but the application is not hang thanks to asynchronous computing).

As mentioned earlier, for monoped on flat ground, the algorithm is faster than real-time. So it’s possible to make it not stuck by maintaining a double-buffer.

Future Works

From now on, I have a working library for use in Unity. Next I’ll

- Set up the double-buffer and think of a way to minimizing the control lag

- Develop a terrain modifier so that users can create their own terrains in Unity

- Implement way points so that users can create a long continuous trajectory